Ionic 2 Tutorial Part 2

13 min · 2522 words

Photo Storage Tutorial Part 2

Writing Unit Tests for your Ionic 2 app

DISCLAIMER

Because Angular 2 is still putting out release candidates at this time (2016-08-23), some of what you see may not be applicable to whatever version is currently out when you read this. I’ll try to update this article when I can if/when a definite testing strategy is put out by the angular team.

Intro

GitHub repo for this tutorial at https://github.com/dually8/Ionic2-Workshop

Hopefully, everything worked out for you in the previous post. Now, we want to focus on writing some unit tests. I’ll go through everything step-by-step again and (hopefully) explain the how and why to you well. Let’s begin.

The Tech Stack

First, I want to take a look at the tech stack we’re using. Here’s what we’ll be using:

- Jasmine, for writing tests

- Karma, for running tests

- browserify, a node module loader for browsers

- istanbul, for code coverage

- isparta, makes istanbul ES6 compatible

- [Optional] PhantomJS, a headless browser in which to run the tests

Bootstrapping tests

Granted, this part has already been done for you, but I want to take a look at how it all works together. Let’s start by opening up test/common-providers.ts. The top is similar to our previous import statements, but we have a slightly different collection here this time.

import { provide, Type } from '@angular/core';

import { Control } from '@angular/common';

import { Http, HTTP_PROVIDERS } from '@angular/http';

import { MockBackend } from '@angular/http/testing';

import { App, Config, Form, NavController, Platform } from 'ionic-angular';

import { Camera } from 'ionic-native';

import { CameraMock, ConfigMock, NavMock } from './mocks';Here, we’re gathering everything we need to import to every test we run. Below this we have two exported arrays: baseProviders and serviceProviders. It’s in these arrays that were going to gather all our requirements for each test we’ll run. Doing it this way makes bootstrapping new tests a lot quicker and will save us time. In between the import and export statements, we have this line:

/**

* Because promises take a long time some times

*/

jasmine.DEFAULT_TIMEOUT_INTERVAL = 20000;We write this because:

- We’re writing our unit tests in Jasmine

- When we use the

asyncwrapper later to test asynchronous calls, we want to give it a bit more time to complete so that our tests don’t fail.

- Note: the timeout interval is in milliseconds, so 20000 would be 20 seconds.

Let’s take a closer look at what the two exported arrays are

export let baseProviders: Array<any> = [

Form,

provide(Config, { useClass: ConfigMock }),

provide(App, { useClass: ConfigMock }),

provide(NavController, { useClass: NavMock }),

provide(Platform, { useClass: ConfigMock }),

provide(Camera, { useClass: CameraMock }),

HTTP_PROVIDERS,

];

export let serviceProviders: Array<any> = [

provide(Http, { useClass: MockBackend }),

].concat(baseProviders);Granted, this might make a bit more sense once we get into writing our first unit test, but real quick, let me explain what we’re doing here. These arrays will be used for dependency injection later. The provide function allows us to inject dependencies that will be mocked. This is super useful when testing things like Http calls.

The next thing I want to look at is app/providers/firebase-provider/firebase-provider.spec.ts (AKA: the first test we’ll be writing). Again, let’s take a quick look at the import statements.

import { addProviders, async, inject } from '@angular/core/testing';

import { provide } from '@angular/core';

import { serviceProviders } from '../../../test/common-providers';

import { FirebaseProvider } from './firebase-provider';The first three things we import (addProviders, async, inject), come from Angular’s testing framework. These are going to let us inject dependencies efficiently (though, that part may be up for debate until they finish their testing documentation). We’re also importing serviceProviders from the common-providers file we looked at a moment ago, and since we’re going to be testing the FirebaseProvider, it only makes sense to import that as well.

Below the imports, we have a little guy, specProviders. Basically, he’s going to hold all the dependencies we need to inject in order to get our tests to work. Some times, this will just be our baseProviders or serviceProviders, but in most cases, we’ll need a couple more things in order to get everything to work. In this case, we need to inject FirebaseProvider since we’ll be testing it, so we come away with something like this:

let specProviders = serviceProviders.concat([

FirebaseProvider

]);Here, we’re putting all of the base dependencies, service dependencies, and one more specific dependency into a single array for us to use at a later point. Below this, we have our first describe block.

describe('FirebaseProvider', () => {

const config = {

// todo: put your own stuff here

apiKey: '',

authDomain: '',

databaseURL: '',

storageBucket: '',

};

firebase.initializeApp(config); // call ONLY ONCE

// ...

});From the Jasmine documentation a describe block says

A test suite begins with a call to the global Jasmine function

describewith two parameters: a string and a function. The string is a name or title for a spec suite – usually what is being tested. The function is a block of code that implements the suite.

Or, TL;DR - Name your test block.

Inside the function part, we have our config and initializer. Go ahead and copy/paste your credentials into that config object, because you’ll need it for later. Next, let’s take a look at the beforeEach block and the first it block (AKA: the first test case).

beforeEach(() => {

addProviders(specProviders);

});

it('should be defined', async(inject([FirebaseProvider], (_fb: FirebaseProvider) => {

// todo: complete this test

})));Real quick, before we hit the beforeEach, let’s look at the it block. The it block is similar to the describe in that we have 2 parameters: a string, and a function. The string is the name of the test you want to give it, and the function will contain the stuff you want to test. The async is a wrapper that tells the it’s function call that this particular call is asynchronous. The inject takes two parameters: an array of providers to inject, and the function to call. Normally, you’d list the providers as parameters in the function call. This will hopefully make more sense as we go along.

The beforeEach block is a nifty little tool that executes what’s inside of it each and every time before a test runs (an it block runs). In our case, we’re using addProviders to add an array of injectables (AKA: providers/services) before each test runs. Note: addProviders is deprecated and it’s recommended to use the TestBed now. As I said in the disclaimer above, this stuff is still being worked out by the Angular team.

Now, inside of the it block, we want to make an assertion. We can do this by calling expect. An expect statement takes a single parameter that is then chained with the actual assertion. You can read a full list of these in the Jasmine documentation. Meanwhile, you can just trust that I’m making the correct assertion calls. Let’s fill in the first test like so:

it('should be defined', async(inject([FirebaseProvider], (_fb: FirebaseProvider) => {

// todo: complete this test

expect(_fb).toBeDefined();

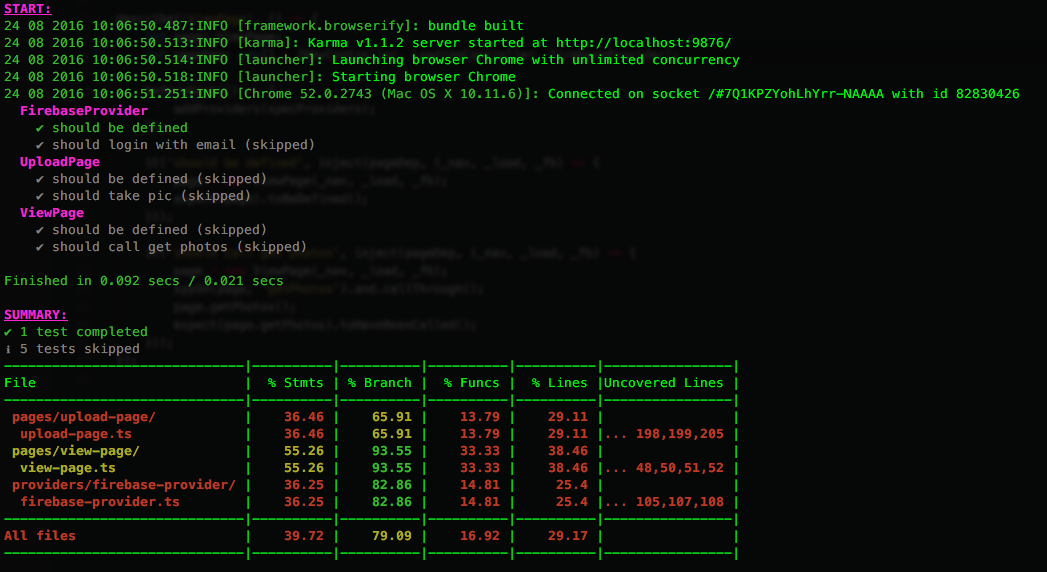

})));If it wasn’t already obvious, we’re making sure that _fb is defined. This is always a good first test because we want to make sure all of our injection things are working correctly. If you like, go ahead and run the test by running npm test. Hopefully, you get an output similar to this.

For now, don’t worry about the skipped tests. I’ll throw in some tricks at the bottom of the tutorial if you’re curious as to how I skipped the others. If this didn’t work for you, feel free to put in an issue here. If it did, great! Let’s continue.

The next test should login with email. So, let’s write this one. Since it’s an asynchronous test, we need the async wrapper again. Your test should look something like this:

it('should login with email', async(inject([FirebaseProvider], (_fb: FirebaseProvider) => {

_fb.loginWithEmail('test@test.com', 'test123')

.then((user) => {

expect(_fb.isAuthenticated).toBe(true);

});

})));Now, the username and password you pass in may be different. This is just a test account I made on my particular app in order to complete this unit test. Go ahead and run your test again and make sure it passes. If it times out, try increasing jasmine.DEFAULT_TIMEOUT_INTERVAL. If that doesn’t work for you, let me know by opening up an issue on this post’s repo.

Hopefully, things worked out for you and/or you just want to continue. The next test I want to look at is app/pages/upload-page/upload-page.spec.ts. As always, we have our import statements at the top, an array of providers below that, and a describe block to tell karma that this is a brand new bag of tests to run. You may have noticed a couple of different things this time around:

describe('UploadPage', () => {

let page: UploadPage;

let pageDep: any[] = [NavController, ModalController, ActionSheetController, ToastController, FirebaseProvider];

beforeEach(() => {

addProviders(specProviders);

});

// ...This time, we’re making two variables at the top of our describe block. One is to hold the class object we’ll be testing, and the other is an array that holds the stuff we put into the pages constructor. Looking back at the upload page class…

export class UploadPage {

// ...

constructor(

public navCtrl: NavController,

public modalCtrl: ModalController,

public actionSheetCtrl: ActionSheetController,

public toastCtrl: ToastController,

private fbProv: FirebaseProvider) {

}

// ...Notice that the same stuff we have in the pageDep array is the same stuff in the constructor for UploadPage. The biggest reason I’ve done that here is because I try my best to follow the DRY principle. Otherwise:

// this line

it('should be defined', inject(pageDep, (_nav, _modal, _action, _toast, _fb) => { // ...

// would be this line

it('should be defined', inject([NavController, ModalController, ActionSheetController, ToastController, FirebaseProvider], (_nav, _modal, _action, _toast, _fb) => { // ...Ekk. I’d like to avoid that. Let’s move on to writing the first test.

it('should be defined', inject(pageDep, (_nav, _modal, _action, _toast, _fb) => {

// todo: complete this test

page = new UploadPage(_nav, _modal, _action, _toast, _fb);

expect(page).toBeDefined();

}));In this case, we’re constructing the UploadPage and checking to make sure it constructed successfully. This may seem like a useless test, but it’s a good first test just to make sure everything is working properly. Let’s now move to the next test.

it('should call getPicture if takePic is called', async(inject(pageDep, (_nav, _modal, _action, _toast, _fb) => {

// todo: complete this test

page = new UploadPage(_nav, _modal, _action, _toast, _fb);

spyOn(page, 'getPicture');

page.takePic();

// because `getPicture` is a private function, we have to check it this way

expect(page['getPicture']).toHaveBeenCalled();

})));In this case, we’re using an async wrapper because of the type of calls we’ll be making. We’re also constructing a brand new UploadPage per normal unit testing guidelines. The next line of code might be unfamiliar to you. The Jasmine function spyOn takes two arguments: the object you’re “spying on”, and the name of the function inside of the object that you want to watch. In our case, we’re looking inside UploadPage (or page) and watching for getPicture to be called. The next line, we call takePic which should later call the private function getPicture. Next, we make the assertion (or, expect) getPicture has been called. Hopefully, it passes for you.

Last page to go is ViewPage, so let’s get to it.

import { addProviders, async, inject } from '@angular/core/testing';

import { provide } from '@angular/core';

import { LoadingController, NavController } from 'ionic-angular';

import { baseProviders } from '../../../test/common-providers';

import { FirebaseProvider } from '../../providers/firebase-provider/firebase-provider';

import { ViewPage } from './view-page';

let specProviders = baseProviders.concat([

FirebaseProvider,

LoadingController

]);

describe('ViewPage', () => {

let page: ViewPage;

let pageDep: any[] = [NavController, LoadingController, FirebaseProvider];

beforeEach(() => {

addProviders(specProviders);

});

it('should be defined', inject(pageDep, (_nav, _load, _fb) => {

// todo: complete this test

}));Similarly to the previous page’s test suite, we have our import statements at the top, an array of providers/services we’ll need next, a variable to hold our constructed page, and an array of dependencies for said page. The first test will look just like the last page’s.

it('should be defined', inject(pageDep, (_nav, _load, _fb) => {

// todo: complete this test

page = new ViewPage(_nav, _load, _fb);

expect(page).toBeDefined();

}));Easy enough? Starting to get the hang of it? I hope so. The next couple of tests are a little be weird looking, but here’s my implementation for the second test.

it('should call FirebaseProvider.getPics when ViewPage.getPhotos is called', async(inject(pageDep, (_nav, _load, _fb: FirebaseProvider) => {

page = new ViewPage(_nav, _load, _fb);

spyOn(_fb, 'getPics').and.returnValue(new Promise((resolve) => {resolve(['pics']); }));

page.getPhotos()

.then(() => {

expect(_fb.getPics).toHaveBeenCalled();

});

})));The first line should look familiar, and at least part of the second line. On the second line, we’re “spying on” FirebaseProvider.getPics, but since we don’t want to actually connect to firebase (we just want to test the functionality of this method), we say .and.returnValue to tell Jasmine that we want to re-write and mock the getPics function. Because we’re only interested in resolving the promise, we just say new Promise((resolve) => { resolve(['pics']); }). Essentially, we’re just saying that FirebaseProvider.getPics should return a string array containing ["pics"]. Now that we have that mocked, we can call page.getPhotos and make the assertion that our FirebaseProvider should have called its getPics method. Hopefully, that worked out for you.

The next test is similar. Check out my implementation below.

it('should return one pic', async(inject(pageDep, (_nav, _load, _fb: FirebaseProvider) => {

page = new ViewPage(_nav, _load, _fb);

spyOn(_fb, 'getPics').and.returnValue(new Promise((resolve) => {resolve(['pics']); }));

page.getPhotos()

.then(() => {

expect(page.myPhotos[0]).toBe('pics');

});

})));Again, we’re mocking the FirebaseProvider.getPics method to return a string array with one element. Because ViewPage should be storing all the strings it gets back from its getPhotos call, we check to see if page.myPhotos contains the same thing we mocked above in the FirebaseProvider.getPics call. Hopefully, that, too, worked out for you.

Well, that’s the end of it. I hope you learned something, and I hope I explained things well enough for you. I recently added Disqus comments on here, so feel free to leave me a comment if something didn’t make sense to you. I’ll try my best to explain it better. Thanks for reading.

Notes

Here’s a few neat little tricks Jasmine provides for you

fit: Run just this test. If two or more are labeled withfit, all with that label will run.xit: Disable (or skip) this test.fdescribe: Run just this suite. If two or more are labeled withfdescribe, all with that label will run.xdescribe: Disable (or skip) this suite.

You can find more in the Jasmine Documentation.